Testing software can often be seen as the least enjoyable part of the systems development life cycle. It is easy to see why. Developing the actual application that does the magic that the end user finds value in is indeed a very exciting core to the process. And yet, what you produce could be worthless if it doesn’t work for the user.

So let’s say you are working on an individual pet project. The fun part is coding it up and getting it to do something. Here, I’m going to use a simple Flask app that serves up some Wikipedia page count stats as an example. As a developer adds layers and new features and new bells and whistles and pipes and extension cords to their project, things which they haven’t developed in months or years can break, and if they don’t have a good testing suite in place, they won’t catch it and will serve out a degraded experience. That’s a dis-service to their users, but even to themselves, whose hard work has gone to waste because that piece of the project, which they might have spent many hours working on, might as well not even exist if it doesn’t work. Worse yet, if they break their app entirely, it could take hours and hours of searching for a bug.

If instead there is a systematic testing suite in place, each incremental change can be subjected to a battery of tests that help ensure that it is safe to continue to the next incremental change. This should not be the developer clicking through their app and making sure everything looks good. There are many awesome tools in place that allow for quick automated testing. Here, we provide a walk through to jump start a web developer on using Python and the selenium and behave libraries to provide a full browser test of their site.

Selenium

Selenium is a Python library that automates testing the final product of a webpage. Selenium integrates with various browsers and replicates the behavior that you expect from your users, all while measuring the response to that behavior against your expectations for how the site, when in its optimal state, should respond. It is as easy to install as

| |

Let’s start with a very simple example. Suppose you have webpage that simply serves this up:

| |

Even if you didn’t want to get fancy and set up a nice file structure and

orchestrate your testing with tools such as behave and nose, you

could simply create a very straight-forward python script that runs

the selenium testing you need to ensure that your page is serving

the expected content.

If you are running these locally on your laptop, the following step isn’t necessary, you will just need to make sure you have Firefox installed. Selenium works with other browsers, but to keep this simple at first, we will focus on Firefox.

Headless on Ubuntu (skip this if using a Mac)

Skip this section if you don’t plan to run this on a remote linux-based server. In this example, I’m using my Cloud 9 IDE account which serves up containers with Ubuntu as the OS.

First we need to isntall the Xvfb package:

| |

and the PyVirtualDisplay python library:

| |

Finally, you’ll need the geckodriver (they don’t include md5sums or rsa hashes to confirm authenticity, but use github to host and release which comes with a great deal of trust):

| |

Our first selenium assertion

Now we are ready for our first test. This test will do two things. First, it will cause selenium to try to access the webpage. If it can’t do so, it will fail. This means that a selenium tests automatically tells you whether or not your page is up and running right out of the box. Secondly, the test will assert that the very simple webpage example shown above is setting the title to ‘WikiViz’ as it should be.

If you are using the headless on your remote server, your code will look like this:

| |

If you are running this in a local environment, such as on a Mac, and you like to watch selenium open the browser and walk through the tests, then your code would look like this:

| |

Yes, it is that easy! OK, well, at least for the title. As your page gets more complicated, so will your testing, but overall the spirit of simplicity in the selenium testing scheme carries over. It’s the complexities of html/javascript that you will eventually need to worry about. But we will keep things simple here.

Expanding the tests

In order to make our example just a little more interesting, and give selenium something to do rather than just observe, let’s add a button to our simple home page that takes us to another page. Add the following just after the h1 entry:

| |

In this next section, I’m going to make the tests a little more

complicated in structure, but for a good payoff. If you like to

keep your tests in a single script as above, you can simply expand

on that script. Here, I will show a simple example using nose

and behave libraries. This example was inspired by a slightly more

complicated (and well done) example (which doesn’t have the headless feature)

here,

but meant to be easier to dive into for those new to testing with selenium.

Create a file structure that looks as follows:

| |

here’s some bash to make that happen:

| |

The simple_examples directory is where I put in some simple scripts

for testing a few features (or writing this blog post), but you definitely

don’t want something that sloppy in a production version of your code.

(Google init python files if you don’t know what those __init__.py files

are for.)

Step One: Define the Behavior

BDD development would have us define behaviors we expect of the site before we even begin to develop site. That’s a good place to start for selenium testing as well, where if these definitions are pre-existing, we can use them as our starting point. If not, we can easily create our own.

In the features directory, create a file called clickbutton.feature with

the following content:

| |

This is the beauty of the behave library and behavior based testing in general.

We can use everyday language to describe our user’s experience, and then translate

that in to tests as we will see shortly. This enables non-technical folks to

contribute tests.

Note that in the above tests, the last line entry is a bit of a cheat on my part. The test really should, in that line, confirm in some way that it made it to the results page. So don’t do what I did there! If for example you click on the button and it takes you to a 404 error page, your test will still pass. I take that shortcut here only to keep this jump start example focused on a single simple html page.

Step Two: Turn the Behaviors Into Steps

In the steps folder, create a file called clickbutton_step.py. Note that

it has the same prefix clickbutton as the corresponding features file we

created above, that is required for each feature file. The contents of this

file will have:

| |

So the pattern here is starting to become clear:

| |

We have chosen to create the steps before the page functions here because that is a natural way to proceed. The steps will tell you what functions you need to create, and then afterwards, create those functions with the narrow scope defined by the steps.

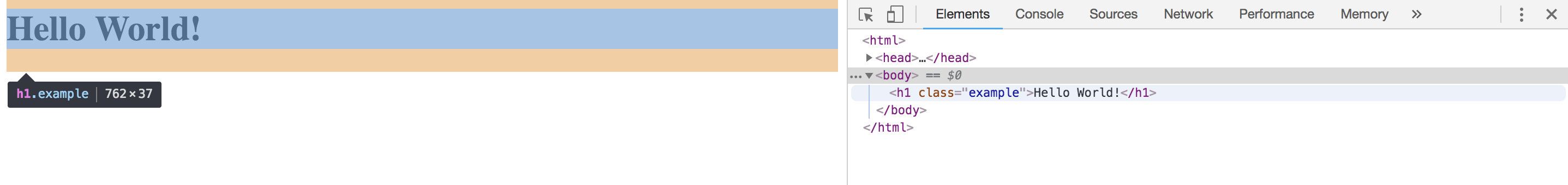

Step Three: Turn the Steps Into Implemented Functions

Let’s stick with our simple home page as detailed above. We can look behind the curtain of this page by using our browser’s developer console. On Chrome, for example, it is in settings > More Tools > Developer Tools. This gives you many great tools to inspect the code and help you locate elements in your code. For our simple example, that isn’t so necessary, but as this example is expanded to include javascript which makes the page more dynamic, these developer tools become very useful. In this screenshot below, for example, we see how it helps us identify elements of the code.

These elements become key as we find key elements to use in our testing.

In the pages folder, create a file called home_page.py with the following content:

| |

Because the source code of our simple page assigns the first and only

h1 header by giving it the class “example”, that makes it easy

to find_element_by_class_name. If in fact we had multiple h1 elements

with that class, we would have to use the plural find_elements_by_class_name

instead, which returns a list that we could submit for testing (e.g.

we would know what the first h1 should be, the second, etc.).

So for our homepage, we have created the HomePage class, which inherits the Browser class we created previously, and we define the actions we will need on this page for testing. When we add other pages to our example web app in later blog entries, we will create a new file in the pages folder, one for each page. In this way, we keep the details nice and cleanly compartmentalized. If we have a subset of pages that share much in common, we can create a class for that subset, and then have individual pages inherit that class, and so on.

Also note that there are multiple ways we can identify elements, including

xpath. In this file, we add four tools associated with our homepage.

The first is a navigate function, the second returns the pagename,

the third returns the h1 element, and

the fourth clicks on the button we just added that will send us to a new page.

Step Four: Define The Browser

Before we can make use of the defined behaviors and expectations, we need to set up our browser and display (for headless).

Create the file features/browser.py with the following content

if you want selenium to run on your laptop or desktop in a way

that you can watch it run through the tests:

| |

Here, I’ve made the page timeout ten seconds because if my page is taking longer than ten seconds to load, to me that is a pretty good reason for it to fail. I would actually recommend you being more generous than not, and instead build in timing features to test for load time rather than have the tests timeout as an indication that your page is slow, but again, this is meant to be a baseline example.

For those wishing to use headless testing (on a remote server, no live browser to watch), the above file will look like:

| |

Step Five: Putting it all together

Finally, we need to have an environment definition to tie everything together.

This will tell behave what page classes to import and tell it what to

do before and after the tests are ran.

If the features folder, create a file called environment.py with the content:

| |

In the folder above features, assuming you’ve installed behave via pip already,

simply run behave. If all goes well, we get an output that indicates the tests

ran and their pass/fail status:

| |

Find the code here

For your convenience, the selenium code is collected here.